Options to Improve the Financial Condition of the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporationfs Multiemployer Program

August 2, 2016 - CBO

The pensions of some 10 million people are insured by the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporationfs multiemployer program. CBO projects future claims on the program and losses to its beneficiaries and analyzes potential policy changes.

ySummaryz

The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) is a government-owned corporation responsible for insuring the benefits of 41 million people who participate in defined benefit pension plans provided by private employers. About 10 million of those participants are covered by plans offered by groups of employers; such plans are insured by PBGCfs multiemployer program. That program has drawn increased scrutiny from policymakers in recent years because of the high likelihood that it will not be able to meet all of its insurance obligations, potentially causing participants to lose insured benefits or putting pressure on the government to provide PBGC with greater federal resources. CBO has projected the claims on PBGCfs multiemployer program—which are likely to be relatively small in the coming decade but are projected to be much larger in the following decade—and has analyzed options for improving the programfs finances.

Why Will PBGC Probably Be Unable to Meet All of Its Future Insurance Obligations?

Many multiemployer pension plans have large funding shortfalls. In all, multiemployer defined benefit plans have promised nearly $850 billion worth of benefits to their participants but have assets worth only $400 billion. Most plans with shortfalls hope to make up their funding gaps by earning investment returns on their assets that outstrip the growth of their liabilities and by getting larger contributions from participating employers. However, a small but growing number of multiemployer plans—which together have $100 billion in liabilities but only $40 billion in assets for about 1 million participants—have reported that they will probably not be able to make up their shortfalls. If so, those plans will eventually become insolvent (lack enough liquid assets to pay immediate obligations) and will file claims for financial assistance from PBGC. Those claims are likely to exceed the resources that PBGC will have available to pay them.

PBGC funds the costs of the multiemployer program from the premiums that plans pay for its insurance and the interest it earns on that premium income. Premium levels are set in federal law, as is the maximum amount of an individualfs pension benefit that PBGC guarantees. That maximum insured amount equals about 60 percent of the promised benefit in a typical multiemployer plan. However, by law, PBGC can pay financial assistance claims from insolvent multiemployer plans only to the extent that the premiums and interest it has collected under the multiemployer program allow. Because those funds are projected to equal only a small fraction of the looming claims on the program, many beneficiaries in insolvent plans would receive less than their maximum insured benefit.

The rules that govern how pension plans are funded expose PBGC to the risk of large losses—losses that would far exceed the corporationfs ability to absorb them. Most multiemployer plans use risky investment portfolios to fund their benefit liabilities, which makes PBGC vulnerable to the risk that many plans will become significantly underfunded when returns on those investments are low during economic downturns. (A plan is said to be underfunded if the current value of its assets falls short of the value of its liabilities.) Moreover, the regulations that specify the minimum amounts that employers must contribute to their pension plans include various exceptions that can lead to the insolvency of underfunded plans. Thus, the holding of risky portfolios increases the risk that plans will become insolvent and file claims with PBGC.

In addition, the use of risky portfolios allows employers to promise a larger amount of benefits for a given amount of contributions than they could if a plan held less risky investments, which would be more certain to meet the planfs benefit liabilities. Under those rules, the higher return that a planfs actuaries expect a riskier investment to yield, on average, is treated as funding the promised benefit with certainty, despite the risk that asset values could fall short of those expectations.

How Much Are PBGCfs Insurance Obligations Expected to Cost?

The cash flows of PBGCfs multiemployer program are tracked in the federal budget, with claims recorded as federal outlays when they are paid and with premiums and interest recorded as offsetting collections when they are received. CBO routinely projects the budgetary effects of the multiemployer program over the coming 10 years on a cash basis as part of its current-law baseline budget projections. The baseline includes projections of claims that PBGC will be able to afford to pay as well as claims that PBGC will not have the resources to pay. In this report, CBO projects claims on the multiemployer program over 20 years instead of 10 years to capture the large amount of claims expected to occur in the second decade.

Those cash-based estimates, however, fall short of being a comprehensive measure of the value of the programfs claims, for two reasons. First, plans that become insolvent in the next 20 years will have considerable insurance claims extending beyond that period. Second, cash estimates do not capture the cost of bearing the market risk that is embedded in the market values of assets used to fund pension plans and in the insurance claims that depend on the value of those assets.

In this report, CBO supplements its cash estimates with fair-value estimates, which incorporate all of the projected claims associated with plans that become insolvent over the next 20 years and which account for the cost of market risk. The fair-value estimates express, in present-value terms, the lifetime value of projected claims, net of premiums received, for all multiemployer plans that become insolvent in the next two decades. Those estimates can be interpreted as the amount that the government would need to pay a private-sector entity today to cover any shortfall between the lifetime claims from those plans and the premiums received by the program.

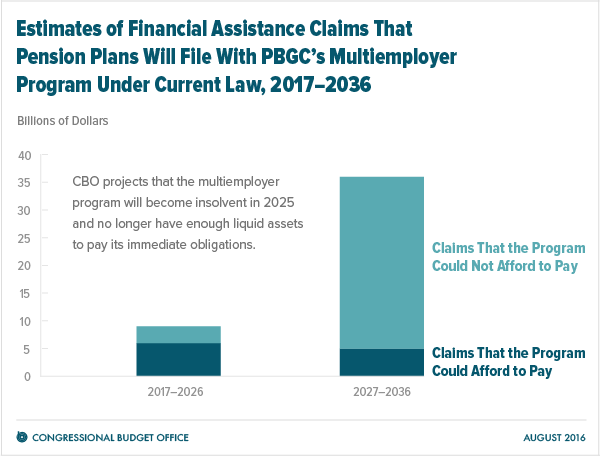

Cash-Based Estimates. Claims for financial assistance from the multiemployer program—which represent amounts that PBGC would be obligated to pay to insolvent plans to cover the cost of guaranteed benefits—are projected to total $9 billion from 2017 through 2026, CBO estimates (see figure below). However, under current law, the multiemployer program is projected to become insolvent in 2025 for the first time in its history. In that case, $3 billion of those claims for financial assistance would not be paid, limiting projected outlays for the program to $6 billion over the 2017–2026 period. (All of CBOfs cash-based projections for PBGC are probability-weighted averages from an estimated distribution of the cash flows that will potentially be realized in the future.)

Claims for financial assistance are projected to be much larger in the following decade, totaling $35 billion from 2027 through 2036. But only $5 billion of those claims (equal to the value of premiums expected to be collected over that period) would be paid under current law if the multiemployer program becomes insolvent in 2025 as projected. In total for the 20-year period from 2017 through 2036, CBO projects a shortfall of $34 billion on a cash basis between claims filed with the multiemployer program ($45 billion) and resources available to pay them ($11 billion).

Fair-Value Estimates. On a fair-value basis, the present value of claims for financial assistance, net of premiums received, over the 2017–2036 period totals $101 billion. That significantly larger estimate can be viewed as the amount a private investor would require to assume PBGCfs obligations to pay all future claims under the multiemployer program for insolvencies that occur during the next 20 years.

How Much Are Participantsf Benefits Expected to Decline?

Many participants in multiemployer plans are expected to receive pension benefits lower than their promised amounts, for three reasons. First, under certain circumstances, plans are allowed to reduce benefits when they are facing insolvency. Second, when plans become insolvent and file claims for financial assistance from the multiemployer program, they are required to decrease their benefits to the maximum amount insured by PBGC. Those two factors are projected to cause the total benefits paid by multiemployer plans in 2036 to be $5 billion lower than currently promised. That decline reflects a projected reduction of 49 percent in benefits from plans that are estimated to be significantly underfunded in 2016 (plans whose assets equal less than 65 percent of their liabilities) and a 6 percent reduction in benefits from plans that are not significantly underfunded in 2016. Third, the projected insolvency of the multiemployer program in 2025 would further reduce benefits for participants—by an additional $4 billion in 2036, CBO estimates.

How Could Lawmakers Improve the Finances of the Multiemployer Program?

In 2014, lawmakers enacted changes to shore up the multiemployer program, including raising premiums, allowing some significantly underfunded plans to reduce benefits (with the approval of PBGC and several federal agencies), and giving PBGC more flexibility to help merge or partition troubled plans. Those changes modestly improved the outlook for the multiemployer program, but claims for financial assistance are still projected to greatly exceed the programfs resources over the next 20 years.

Policymakers and others have proposed additional changes to improve the financial position of PBGC and the overall health of multiemployer pension plans. CBO analyzed the effects of several types of proposed changes and concluded the following:

- PBGCfs ability to pay projected claims could be improved by altering the terms of its insurance or plansf funding rules. Sharply raising premiums, reducing the maximum benefit amount that PBGC guarantees, increasing employersf contributions to significantly underfunded plans, or requiring better-funded plans to make sure their funding equals the market value of their liabilities and to curtail the riskiness of their investments could improve PBGCfs finances without imposing costs on the federal government. However, employers that have better-funded plans can sometimes afford to withdraw from those plans, so options that rely primarily on larger contributions from employers are not likely to improve the outlook for the multiemployer program as much as options that also impose sizable losses on beneficiaries.

- Providing federal funding to PBGC would enable the corporation to partition more troubled plans than it can under current law. In a partition of a troubled multiemployer plan, some of the planfs liabilities are transferred to a new PBGC-supported plan, thus helping the original plan remain solvent. Under current law, PBGC cannot approve a partition if doing so would impair its ability to pay claims from other plans, which sharply limits the number of viable partitions for severely underfunded plans. To create viable partitions for the most troubled plans (which have total benefit liabilities of $81 billion), PBGC would need to receive $10 billion in federal funding, CBO estimates. Those partitions would be accompanied by cuts in benefits, so the projected reduction in claims—and hence the improvement in the financial position of the multiemployer program—would exceed the $10 billion federal cost over time.

- The federal government could recapitalize PBGC to allow the corporation to pay all of its claims. As described above, CBO projects a shortfall of $34 billion between claims filed with the multiemployer program over the 2017–2036 period and resources available to pay them under current law (CBOfs cash estimate). Federal assistance in that amount would be sufficient to cover the programfs projected claims on a cash basis. To cover the lifetime claims of all plans projected to become insolvent from 2017 through 2036 (CBOfs fair-value estimate), private investors would demand $101 billion, which reflects the fact that losses could be significantly larger during an economic downturn. (In addition to recapitalizing PBGC, the federal government could fully or partially privatize multiemployer pension insurance, in which case premiums would be more likely to cover the cost of that insurance and reflect the risk posed by individual plans.)

Some options, such as providing federal funding to PBGC, would be effective at helping plans that are facing insolvency in the near term. Other options, such as restricting plansf investments in risky assets, would help prevent currently well-funded plans from becoming underfunded in the future but would have a limited effect on plans facing insolvency in the near term.

A number of other considerations are relevant to lawmakers weighing such changes. First, the savings from such options would come mainly at the cost of participants—who already face the prospect of large reductions in their benefits under current law—or at the cost of employers, increasing their incentive to withdraw from their plans. Second, cash-based and fair-value estimates of the projected effects of an option can differ greatly because of the adjustment for market risk in fair-value estimates. Third, neither type of estimate includes an optionfs effects on federal tax receipts. (Those effects can be large, particularly in shifting revenues between years, but they are difficult to estimate for various reasons.) Finally, the estimates are highly sensitive to the uncertainty surrounding several parameters of the model that CBO used for this analysis.